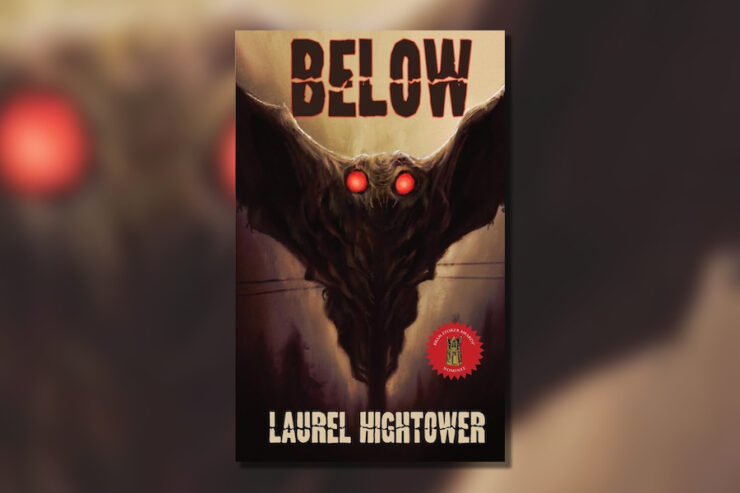

Thanks to the commenter who recommended Laurel Hightower’s short novel in connection with the Mothman phenomenon; it’s just what I was looking for. It captures the mood of the legend: it’s dark, mysterious, and at times horrific. It reads to me as a dialogue with The Mothman Prophecies—both book and film—taking the elements of the story and viewing them through the lens of the horror genre.

Addy, the protagonist, is newly divorced. She’s driving alone through the mountains of West Virginia to attend a horror convention. Friends are waiting for her, and she’s looking forward to a future free of her obsessively controlling ex.

Brian, the ex, spent thirteen years trying to turn Addy into a weak shadow of herself. It’s a classic abuse scenario: isolating the victim, destroying their ability to function apart from the abuser, rendering them helpless to think or act for themselves. Addy is driving alone to the convention to assert her independence. She needs to do this, because Brian would have convinced her she can’t.

Brian is still very much with Addy as she drives. His voice fills her head. He weighs in with negative comments on everything she does. She steels herself to ignore him, but he never shuts up.

Addy needs to get to her destination before dark: her night vision is poor and the road is winding and steep. To make matters worse, the weather is deteriorating. There’s a snowstorm coming, and she hopes she can get through the mountains before it hits.

She nearly crashes into a vehicle stalled across the road. The driver is a disturbing figure, a man in black, whose face is set in a rictus grin. The encounter leaves her deeply shaken.

She stops at a truck stop to pull herself back together. There she meets a trucker, an affable guy named Mads, who offers to convoy with her to the nearest lodging, thirty miles away. This part of the road is a notorious dead zone for cell signals, and it has a reputation for weirdness.

Mads loans her a CB radio and regales her with his life story while the dark closes in and the storm worsens. His easygoing, cheerful voice almost drowns out Brian’s litany of her flaws and failures.

On the steepest, most treacherous section of the road, in a blinding blizzard, a huge, shadowy winged creature with glowing red eyes looms up ahead. Mads’ truck skids off the road, which at this point is a bridge over a chasm of unknown depth, and Addy’s car almost follows it. There’s no cell service here, and no way to call emergency services.

In a logical world, Addy would leave the scene, drive until she has cell service, and make the call. But this is horror world. The CB comes alive with Mads’ voice—it seems he survived the crash. Addy leaves her car and makes her way down into the ravine to try to help him.

And then things get worse. Much, much worse. And much stranger. Much more ghastly, too, shifting quickly from weird and frightening to outright horrific.

Hightower shows a clear familiarity with both John Keel’s book and the 2002 film. Addy’s drive through West Virginia recalls film-John’s strangely time-shifted detour to Point Pleasant, with echoes of his wife’s Mothman sighting and the car crash that results from it. The creatures Addy meets are familiar from John Keel’s investigations: Mothman, the Men in Black, the grinning man, the secret—maybe government, maybe not—experiments. And, inevitably, strange lights in the sky, whether they’re UFOs or, as John Keel believes, some form of interdimensional phenomenon.

Addy never gets answers to her questions. Who is Mads, really, and why is he transporting such peculiarly awful cargo? Who is the grinning man and what does he want, besides Addy’s silence about what she’s seen and experienced? What is the red-eyed monster, and why is it stalking her? What are the things in the cave, and how and why does its entrance disappear once she ventures inside? What are the lights in the sky? Where do they come from, and what is it all for?

In the end, none of it really matters. Addy’s journey isn’t about investigating the paranormal. It’s about freeing herself from a lifetime of learned helplessness, and making her own way forward. Every challenge she meets, every horror she encounters, helps her to find her strength.

It’s an interesting read after the film and Keel’s book. The film is a personal journey, too. It fridges John Klein’s wife (who sees Mothman in progressively more fevered visions as her brain tumor grows) in order to get him to Point Pleasant in time to investigate the events that culminate in the collapse of the Silver Bridge. John Keel’s journey is much more diffuse, with many more ramifications and side excursions, and no wife to dispose of—but it leads him ultimately to the theory of ultraterrestrials.

For Addy, what matters is her own inner life. The scale is correspondingly smaller and more focused. The town of Point Pleasant and the bridge over the Ohio shrink to a truck stop, a narrow mountain road, and the bridge over Silver Creek. In place of the abandoned chemical plant and the expansive acreage of the wartime installation, we have the cave at the bottom of the ravine. There’s no friendly law enforcement here; the sheriff treats Addy just as all the other men in her life have, except, to a point, Mads: he ignores her, talks over her, and tells her what she saw, regardless of whether she actually saw that particular thing.

John Keel and movie-John are stalked by strange electronic phenomena and eerie, unexplainable voices. They’re primarily external; they’re warnings of disaster and signals from either outer space or another dimension. Addy’s voices are distinctly personal. They’re speaking to her specifically. They either try to diminish her, to render her helpless, or they encourage her to escape from that helplessness.

For Addy, the phenomena that Keel studied and movie-John tried to understand are aspects of her own inner landscape. They show her how to escape from the patterns she’s been locked into. She has to go down deep, and face her worst demons, in order to be born into a new and freer self. Then she can silence the hectoring male voices and make her own way into the light.